The International Sleep Products Association’s first 100 years—Part VII of the third installment

Product trends of the time: Waterbeds make waves, latex supplies dry up and more

BY JULIE A. PALM

Splash down! Constructed and advertised in ways unlike bedding products before them, there was nothing subtle about waterbeds when they crashed onto the shores of the conventional mattress industry in the late 1960s.

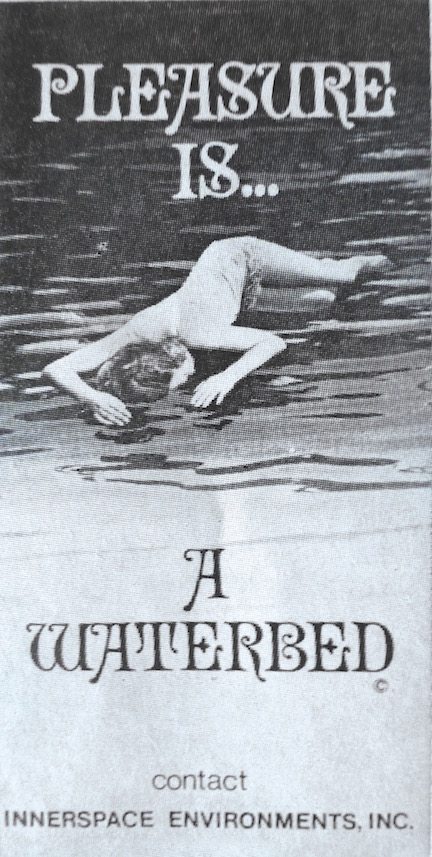

Above: In the late 1960s, Innerspace Environment Inc. introduced its Pleasure Pit, a small waterbed ‘surrounded by leather and covered with fur.’ Below: The company promoted the Pleasure Pit, as well as the Suntanner, a waterbed designed for outside use, in Playboy magazine—confirming to many that waterbeds were gateways to hedonism.

Marketed sometimes as a way to alleviate aches and pains and provide more restful sleep, they were just as often touted as gateways to hedonism. One producer, Innerspace Environment Inc., ran ads in Playboy magazine, a fitting vehicle for a company that offered the Suntanner, a waterbed designed for outside use, and the Pleasure Pit, a small waterbed “surrounded by leather and covered with furs.” Competitor Craft Associates offered a 10-foot by 11-foot waterbed it called Pleasure Island, featuring a stereo system, color TV, lamps and seating, at a retail price of $2,900. (A basic queen-size waterbed of the time was retailing more in the $399 to $499 range.) In 1971, Aquarius Products ran ads in The Village Voice that promised “loving on an Aqua Bed is having silky smooth stimulating ripples of pleasure … each movement echoes back as three, making nighttime an event of total joy.”

There were other issues with the new beds, including consumer concerns about “seasickness” and worries that the beds would leak or, worse, fall through floors because of their weight. In fact, some landlords of the time put language in leases banning waterbeds. Mail-order companies selling essentially a vinyl bag for as little as $26.95 didn’t help the category’s early reputation, Bedding editors reported in April 1971.

In the early 1970s, waterbed manufacturers set out to improve their products—and their products’ reputation—starting with forming trade associations, which hosted product expositions and established construction standards. By 1973, the California Bureau of Furniture and Bedding had adopted waterbed regulations and, about that same time, Underwriters Laboratories began to certify waterbed heaters.

As waterbeds matured in the latter part of the decade, conventional bedding makers, including King Koil, Therapedic, Englander and Jamison, dipped their toes into the category, introducing waterbeds designed to look more like conventional bed sets and adding components such as baffles to reduce motion. Those innovations created a new category, typically referred to as hybrids.

The success, albeit fleeting, of waterbeds helped set the stage for airbeds, which manufacturers had briefly floated as an option in the 1950s, but which were mostly relegated to use in camping. Waterbeds brought improvements to air bladders and opened up a new way for airbed makers to talk about their products: Air flotation systems, they told consumers, were far superior to their watery forbearers. Dial-A-Firm Corp. started producing an airbed in 1978 and later teamed with Restonic, making it the first major conventional mattress manufacturers to offer an air option. Comfortaire introduced its airbed in 1981; Select Comfort, maker of the Sleep Number airbed brand, was founded in 1987.

Latex’s loss, polyurethane’s gain

During this era, latex wasn’t widely used in mattresses, but it was favored by a number of manufacturers who incorporated the component—especially newer pinhole constructions—into cores of higher-end models.

In the 1970s, U.S. suppliers of latex, including UniRoyal, Firestone and others, started to abandon production and, in January 1974, one of the last producers, B.F. Goodrich, announced it was selling its production facilities because of “marginal profitability,” according to a February 1974 article in Bedding. Sponge Rubber Products Co., a subsidiary of Grand Sheet Metal Products and its parent Ohio Decorative Products, agreed to buy facilities in Shelton and Derby, Connecticut, making it the last remaining domestic producer of latex. Then, in March 1975, Sponge Rubber Product’s Shelton plant was destroyed in a massive fire. U.S. mattress makers were forced to turn to B.F. Goodrich in Canada—a costly option with imported latex mattress cores subject to a 15% duty charge, according to an August 1976 Bedding article headlined, “Is There a Future for Latex?”

(The story of the Sponge Rubber Products fire took a dramatic turn when 10 people, including the head of the parent company were indicted by a federal grand jury on charges including conspiracy, dynamiting the plant and interstate transportation in aid of racketeering. State charges, including kidnapping of security guards working at the plant, also were filed. At the time, the FBI called it “the largest bombing ever investigated in the United States” and alleged that the blast was part of an insurance scheme, according to articles in Bedding. The head of the company later was acquitted in both federal and state courts of criminal charges; eight others were sentenced to jail terms ranging from four to 20 years.)

The temporary end of domestic latex production was an opportunity for polyurethane foams to make their way into more mattresses, but first they had a reputation to overcome. Introduced in the 1950s, polyurethane foams (often called just “urethane” foams) suffered from performance and durability problems during their early days, relegating them mostly to institutional and recreational markets and the promotional area of retailers’ floors, according to an October 1975 Bedding article headlined “Urethane Foam Mattresses: Still a Victim of Bad PR?”

The Urethane Foam Institute promoted polyurethane foam for use in mattresses, touting improvements in their formulations and new high-resiliency versions. The component also got something of a boost because improved versions could be used as FR materials to help mattress manufacturers meet the requirements of the federal cigarette flammability standard.

But even into the late 1980s, polyurethanes typically were restricted to comfort layers and the quilt, and not used in mattress cores. In 1986, the Society of the Plastics Industry and the Polyurethane Foam Association worked together on a one-year trial period to educate retailers and consumers about the benefits of foam bedding.

The support of springs

With all the attention paid to water, air and foam during this era, it is important to note that innersprings remained king when it came to bedding constructions. Market share statistics varied depending on whether calculations were made by the U.S. Census Bureau or the National Association of Bedding Manufacturers, but in the 1970s and early 1980s, innersprings represented as much as 92% of the mattresses shipped. “At no time in recent history have innersprings accounted for under 80%” of shipments,” the Association of Innerspring Manufacturers reported in an August 1982 article in Bedding. Advances in automation that made producing coil units faster and cheaper helped secure the component’s place in mattresses. ✦

Softening up

For decades, mattress producers seemed to be in something of an arms race when it came to making ever-firmer mattresses. But, after attending a round of furniture shows, the editors of Bedding magazine noted in August 1977 what they saw as the real beginnings of a move away from “the super-duper-extra-firm” mattress.

Manufacturers weren’t ready to embrace the word “soft,” which they worried brought to mind saggy constructions, but they were trying out phrases like “gently firm” and embracing pillow tops:

“It’s entirely possible that the long-standing push to ever higher levels of firm, firmer and firmest has hit its upper limit, and that the new bedding industry byword will be ‘comfort’.”

Next up

All year, BedTimes has been commemorating the rich history of the International Sleep Products Association and the past 100 years of the bedding industry. We’ll wrap up the special centennial sections in the November issue. We chronicled the first 25 years in March and the second 25 years in June. You can find those reports online at www.bedtimesmagazine.com.

Credits & sources

Research support and assistance provided by Deb Chapman, Dana Jackson and Jasmine Wood. Editorial direction by Mary Best. Art direction by Stephanie Belcher. Primary sources include the archives of the International Sleep Products Association and the industry magazines: The National Bedding Manufacturer (later called Bedding and still later BedTimes) and Bedding Merchandiser.

Read all seven parts of this month’s special ISPA 1966-1990 centennial section:

Part I – Main feature: ‘The challenge of change’

Part II – New directions for mattress industry public relations

Part III – Uniform Monday Holiday Act brings sales, promotional opportunities

Part IV – The industry enters the computer age

Part V – The Sealy wars erupt: Sealy Inc., Ohio-Sealy duke it out

Part VI – Out with the old: Industry works to keep used mattresses out of circulation

Part VII – Product trends of the time: Waterbeds make waves

View this special section as it appears in the print magazine: BedTimes’ August digital edition.

Read previous chapters in the 100-year history of ISPA:

1915-1940: An industry comes together

1941-1965: A time of war, a time for peace